Writing this piece dismantles any assumption of the art critic as someone who can fully consume and dissect the work of a calculating and unruly Black queer artist. With the spectre of COVID-19 and its strain on art criticism, I must admit the invigorating challenge posed by writing about a soon-to-be installed and activated work without the usual rituals of several studio visits — that privileged opportunity for a Black feminist art critic to witness a sibling-comrade’s work emerge from a mess of materials on a studio floor into a thesis-worthy product. This adds another layer of opacity and mystery to Ross’s already-fugitive practice, and thus requires viewers to adopt a speculative and otherworldly method of looking.

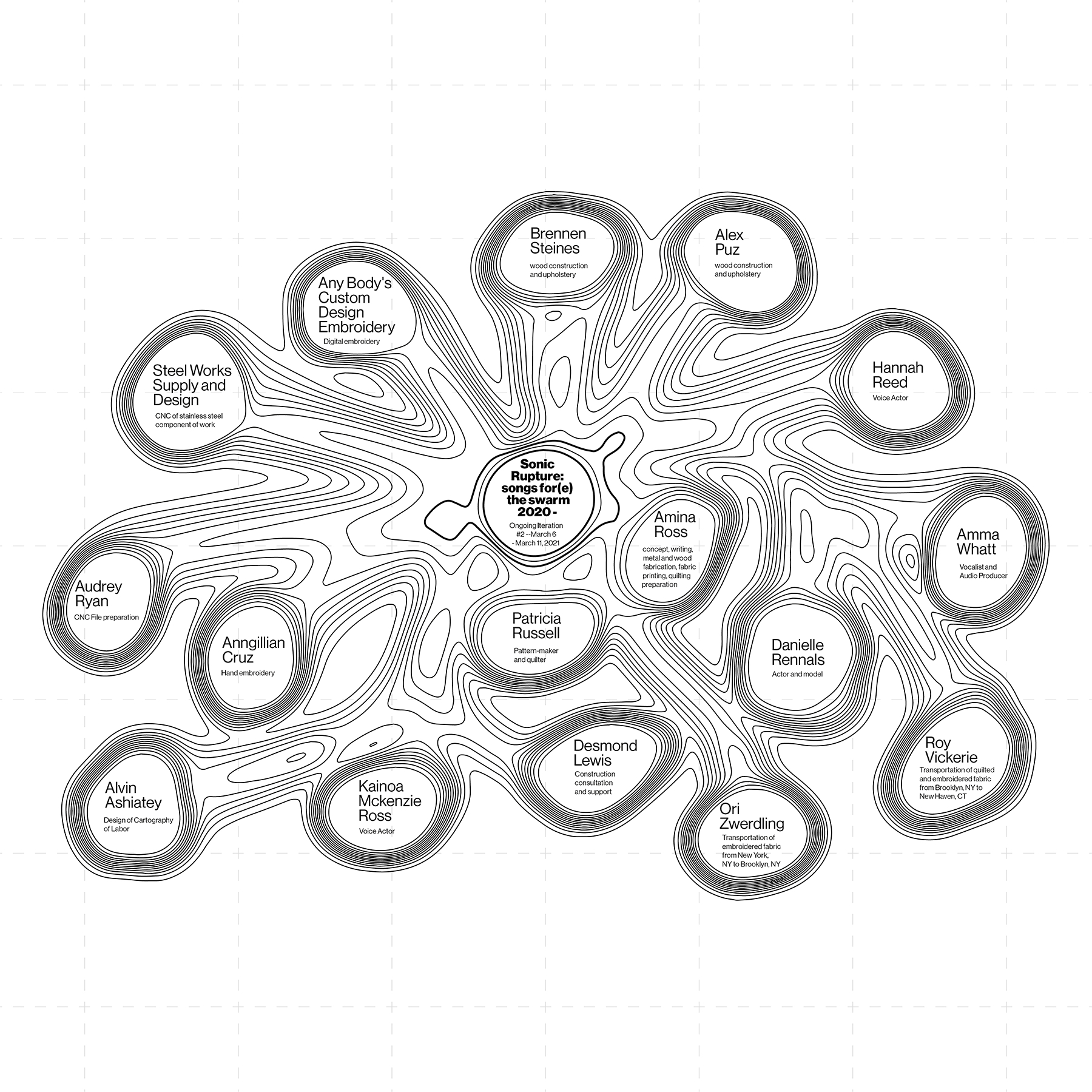

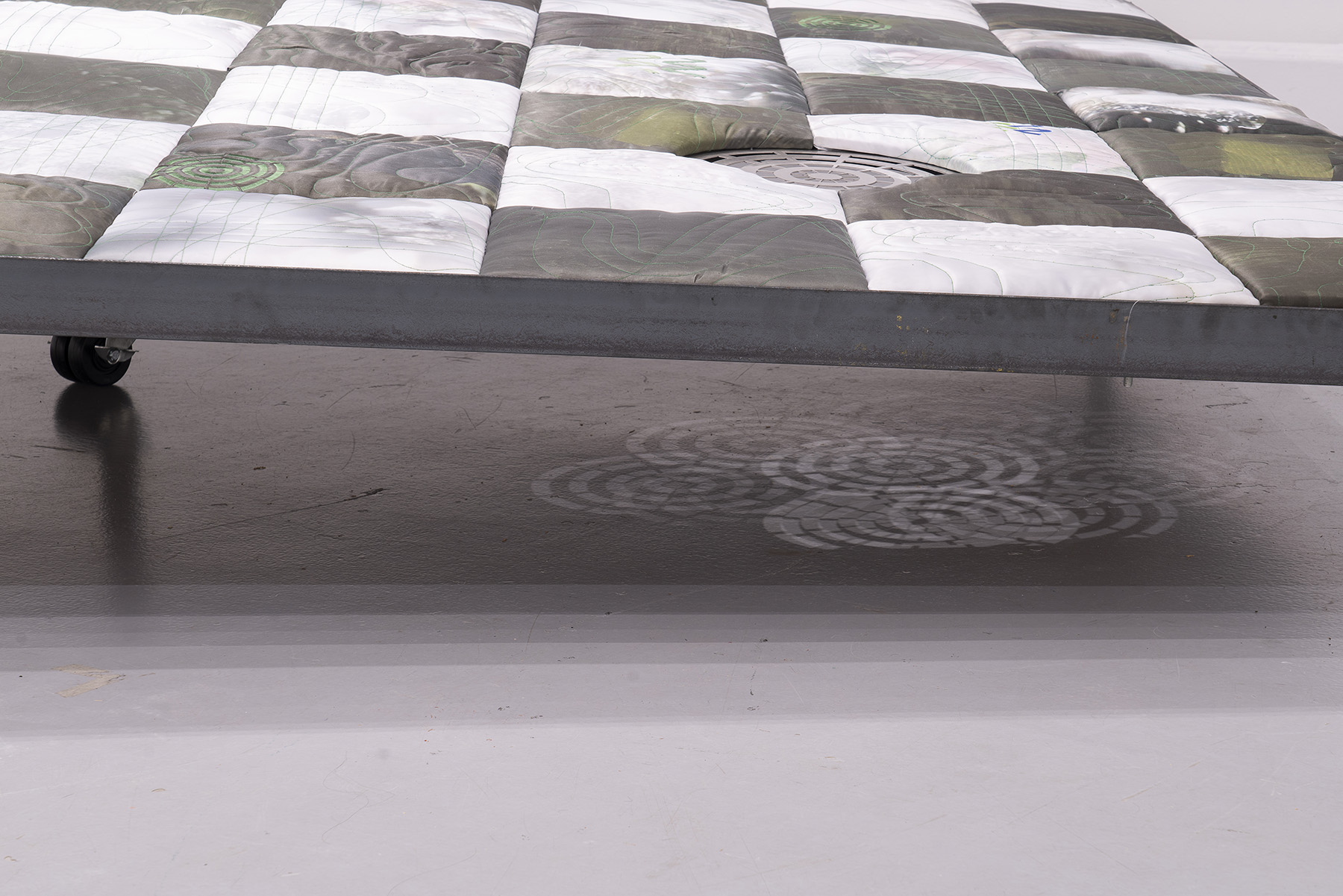

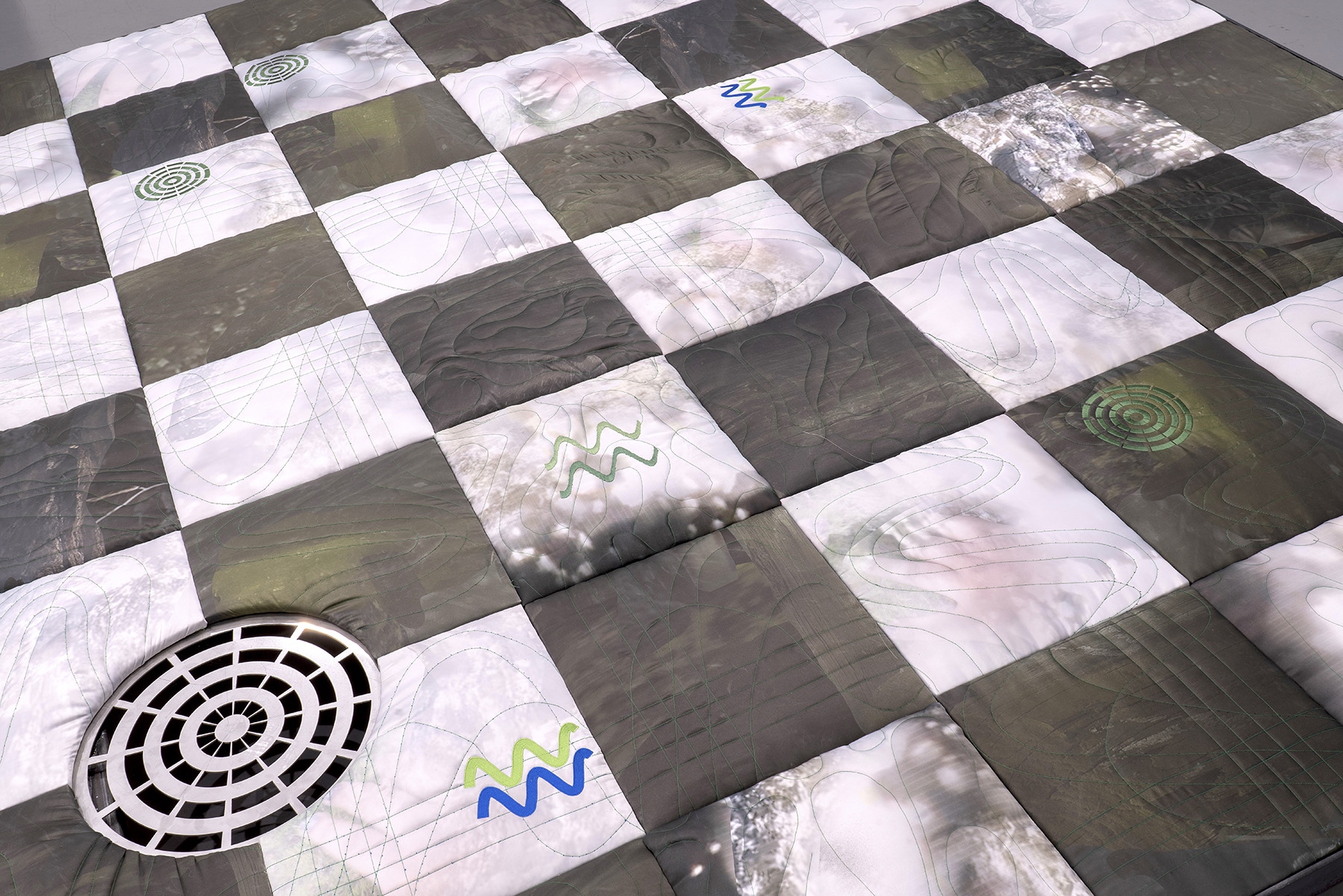

The work is a sculptural installation, a game board, a dance floor, and a bed. Its materialization as a poetic and tangible space invites a medley of fleshy possibilities: dancing, playing, sleeping, loving. Experiencing this during the pandemic gives the work’s haptic and intimate qualities an elegiac sense. The crowded sanctuary of a nightclub, casual romantic trysts in beautiful strangers’ beds, a nostalgia-filled afternoon of vintage board games — all these joyous happenings now feel so ancient. Even before our subjection to pandemic precautions, Ross has maintained a fondness for small-scale gatherings. When I discussed early designs of these newest works with them, the artist referenced the potential of commissioning performers to interact with the dance floor, recorded by a drone. Lens-based technology and embodied performance make their way into Ross’s sculptural imagination. In early plans for the work, a billboard-like screen/frame portrays a still from one of the artist’s moving image works — an outtake from Emotional Weather (2020).1 Not only is this an intertextual reference within the artist’s oeuvre, it also reveals their architectural mind — particularly an interest in supportive architectures. There are beams that hold up the image, but one might ponder the ways in which the bed/game/board/dancefloor hybrid object is supportive architecture as well. I am enthralled by the openness of Ross’s sculptural gesture — their vulnerability in building a space on which our political, affective, and erotic desires can act. Such a metaphor risks tautology, but there is a painterly language here, beyond the cursory understanding of a blank canvas to be filled. The abstraction — curvaceous lines and subtle, earthy coloring — of the dance floor itself is the gorgeous offspring of a painterly gaze. These mythical bodies at play on the game board or sleeping/loving on the bed further animate the quilted floorboards much like a dynamic brushstroke energizes a canvas. Ross themself is always in motion — contemplating their next experiment with crafting psychic and physical spaces for us to enter. Said lovingly, there is no way to keep up with Amina Ross.

1 Amina Ross, Emotional Weather (2020).

How do we map our own desires onto this structure? In essence, it almost becomes a stage for us to act out our own curiosity and delights regarding what embodied and affective interventions can be rendered in the gallery space. We must take heed the poetic insights Ross yields about bodies, the built environment, and an aesthetic object that continues to blossom through the yearning of the viewer.

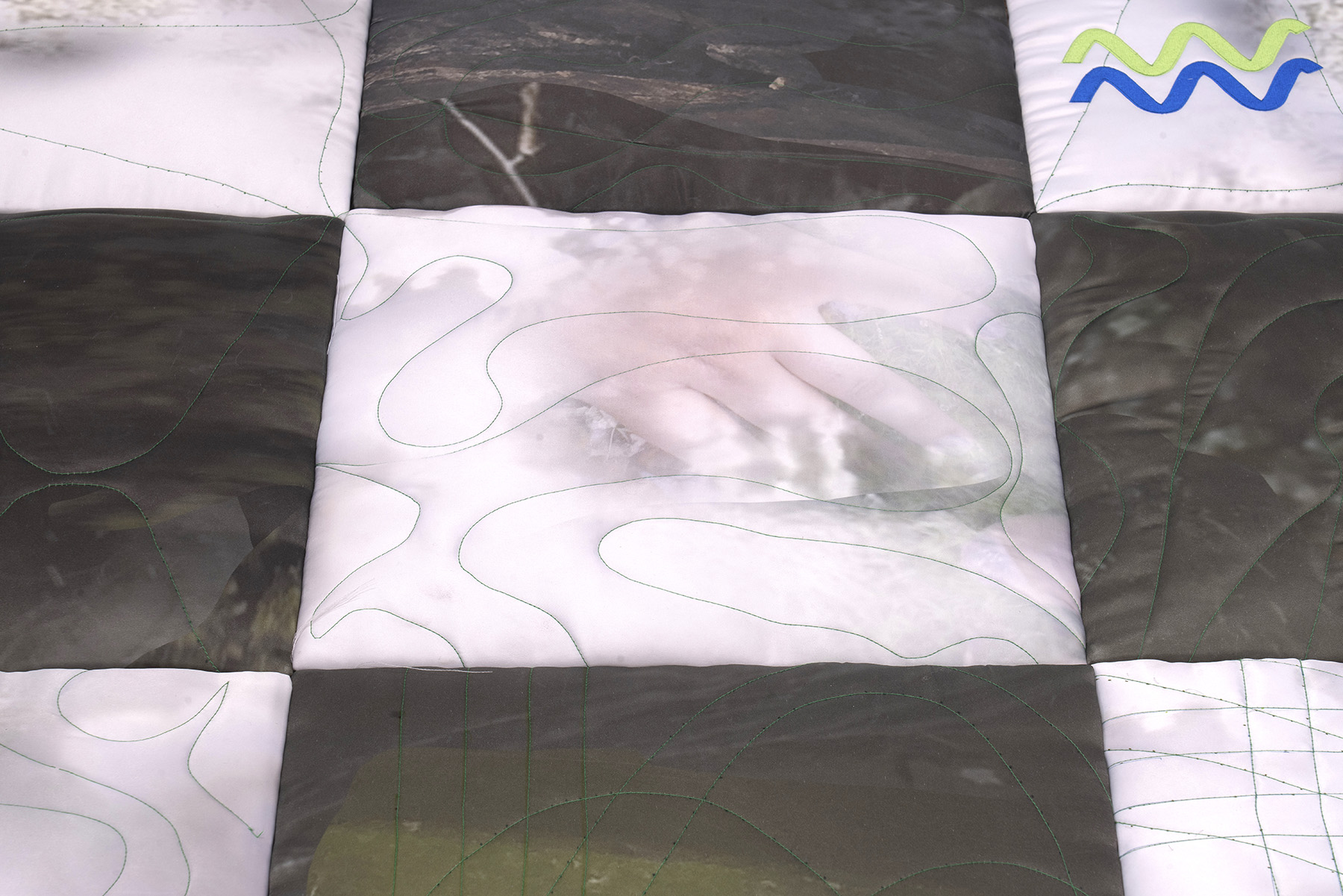

The anticipated hardened laminate of a nightclub dancefloor is instead supplanted by quilted fabric tiles that do not support but rather surrender to the body’s mass, each padded square a mossy abstraction of dappled light-made material. Entering Ross’s installation is a submersion into queer time, where future and past are not relational but simultaneous. There is no sacred teleology here; it all occurs at once, like the layered syncopations of disco.

Whereas digital renderings are the cybernated media of our present and future, quilting is an ancient labor. Over time, this patient practice has been subject to gendered and classed markings — “feminized,” “functional,” “folk.” Ross’s digitally-printed fabrics suggest that quilting is a technology, domestic ingenuity that meets our needs for warmth as well as ornamental decadence, muddling the line between function and desire.

Quilts are intimate aesthetic objects that stack up at the end of bedframes, heirlooms passed down through generations’ hands. Here, it is not merely the quilt as an object that has been passed down, but the process of its own making: each quilted tile has been judiciously crafted and designed in collaboration with their grandmother, Patricia Russell. This embodied act of intergenerational communion tesseracts time to produce a quilt manifested by stolen time, queer time, black time, time wrestled back from the grips of linear progression. Incidentally, the same can be said for dancing, or for sleeping.

When Ross and I talk about their grandmother’s hands, I am reminded of the Freedom Quilting Bee, a sewing cooperative that produced polychromatic quilts for generations in a small hamlet south of Selma along the Alabama River. In 1972, Sears Roebuck and Company contracted the Freedom Quilting Bee to produce simple corduroy pillow covers at scale.2 Embarrassed by idiosyncrasy, white Sears patrons wanted something systematic, compelling the quilters to standardize their individual touch for something nearly machine-manufactured. Working against this tendency towards standardization, Ross animates the principle of quilting’s striking inconsistencies, where mathematized patterns are rearticulated through individual vision and desire; in quilt-making, sewing patterns are not inviolable law but a choreography that yields to improvisation.

2 Arnett, William, Paul Arnett, Joanne Cubbs, and E. W. Metcalf, Gee's Bend: the architecture of the quilt (Tinwood Books, 2006), 91.

Ross’s installation is alive with affectionate human entanglement, ripe with the tantalizing uncertainty induced by chance encounters. On this platform of intimate relation and under darkness, whether a bed, a dance floor, or a gameboard, the next question remains the same: “whose move?”

A child’s voice haunts the space with such poetic overtures: “Living inside the specter of the present we go to war everyday and still find ways to be together.” Here, the mechanisms of quilting reveal a takeaway: through violent puncture, a needle sutures two soft pieces together. We find our needle and our stray pieces and we yoke them.

These short essays were conceived of as sister-pieces. While they are separately authored, they reflect a collaborative process of thinking, editing, and feeling with and through Amina Ross’s practice.

aminaross.com