Two salt licks hang parallel the viewer like cuneiform tablets whose undulating depressions suggest that they were carved by cows — lick by lick by lick. In their fleshly colour and solid form, these wonderfully errant impressions index a body, specifically the organ endowed with the capability of speech. But who here speaks — human or animal?

The salt lick is a curious object. It can be artificial or natural; small piles scattered in the forest soil, or opaque rose-colored blocks that dangle like Christmas ornaments on fence posts. These mineralized spaces invite all kinds of creatures to congregate: horses, cows, sheep, deer, moose, porcupine, foxes, tapirs, and humans alike may share encounters with each other — encounters which might be at once transitory, lingering, violent, and tender.

As long as humans and non-humans have been in contact, salt has mediated many of these encounters. Historically, the paths animals made to natural mineral licks became main trails for early humans, which then became modern highways, which were then again salted to preserve modern road conditions.1 As a long-held agricultural practice, farmers present their cows, sheep, and horses with salt licks as a way to provide nutrients they wouldn't get otherwise. The salt lick then, is a point of encounter, but its ubiquity also speaks to the anthropocenic shifts within our ecosystems.

Some viewers will be confronted by the bodily proportions of Ryan’s salt licks. To look squarely at their bovine impressions, at eye level, is to experience an intimate, physical sense of similitude, affinity, and even kinship with its makers.

Ryan’s oeuvre theorizes a kind of deromanticized kinship between humans and nonhumans while accounting for the affective complications of its constitutive encounters. Critically, Ryan’s sculptures create a vacuum of legible mythologies or linear stories to be told about the objects with which she presents us. Two comet goldfish prepare for a fight, unknowing adversaries in cheap plastic bags. A viewer investigates the sensorial suggestions of seagulls eating cheerios, only to find themselves trapped by their unreliable narrator. These engagements are mostly absent of physical bodies, yet their presences linger in material residues: cheerios, feces, plastic, salt. Merely ghosts — of cattle, of gulls, of humans–remain fixed in space.

Donna Haraway writes that, “Without sustained remembrance, we cannot learn to live with ghosts and so cannot think.”2 In preserving these liminal spaces and these epistemological gaps, Ryan’s work invites us to remember the ghosts with which we live. We are allowed to keep the mystery, to tend to our desires, and to stay with our ghosts — troubled as they may be.

1 “Mineral Lick,” (2021, January 16) in Wikipedia.

2 Donna Jeanne Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. (Duke University Press, 2016), 39.

Audrey Ryan’s sculptures entice their viewers to navigate loci of desire: like stages set for the many encounters between creatures and that which they might consume, subsume, excrete, occupy, and destroy.

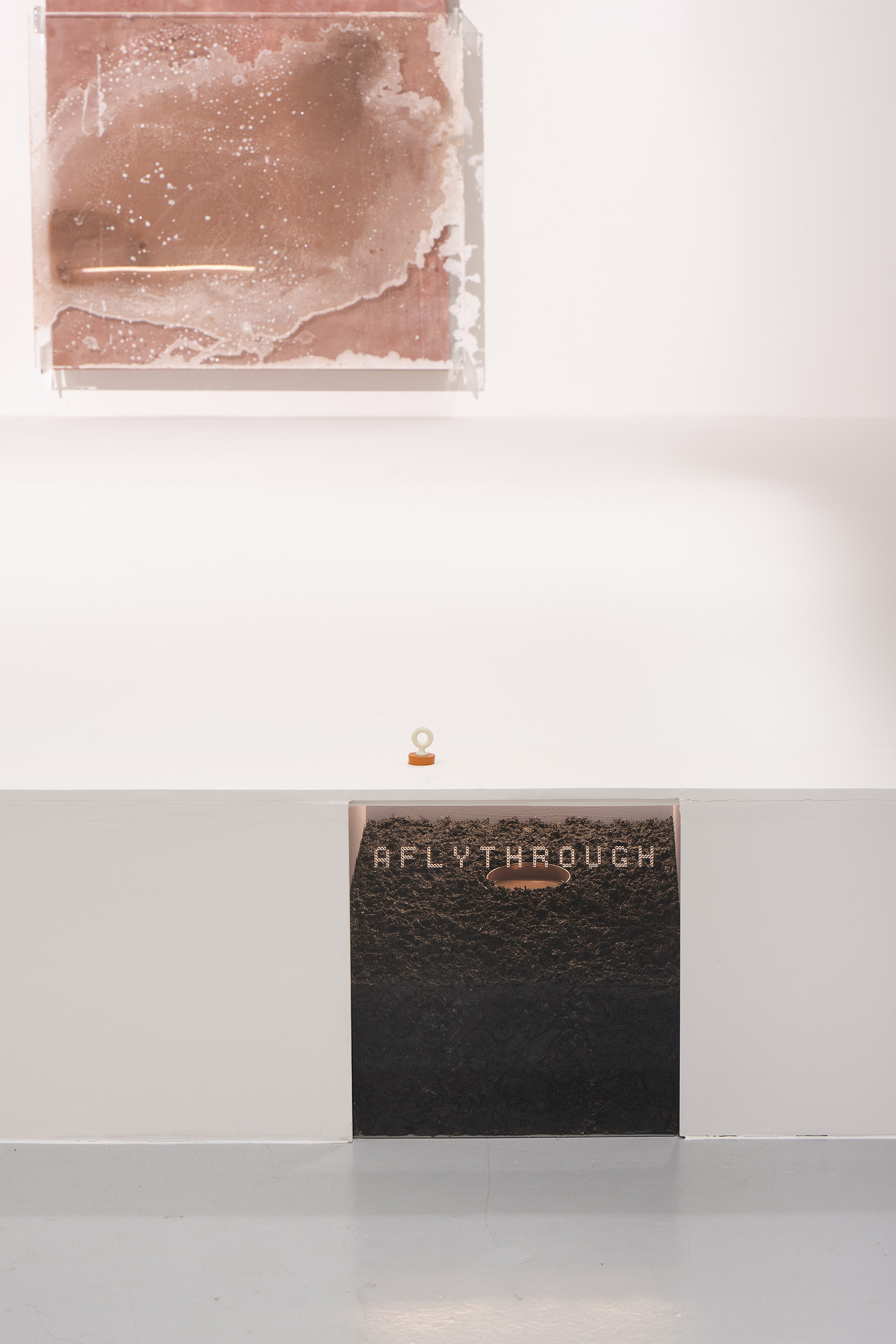

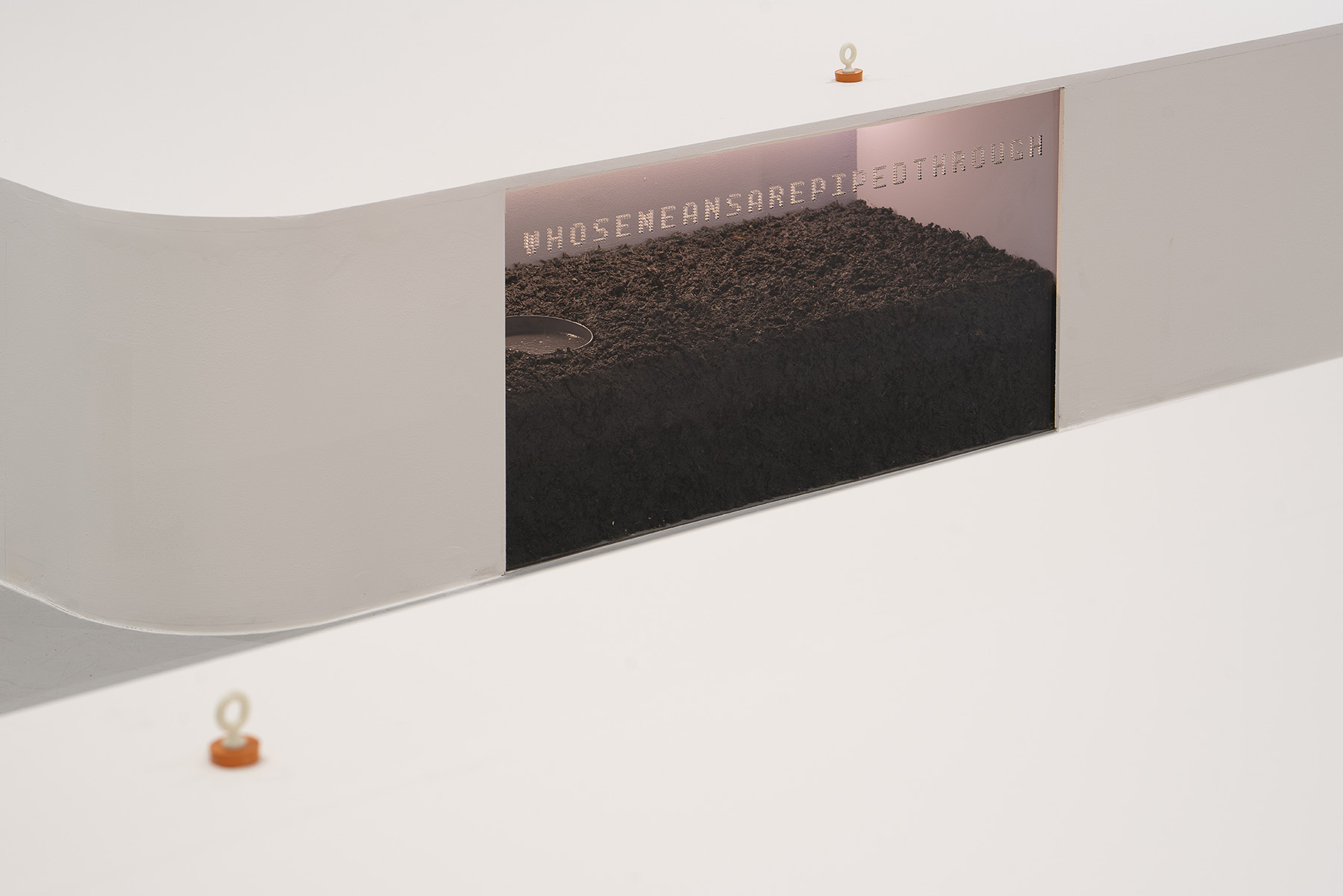

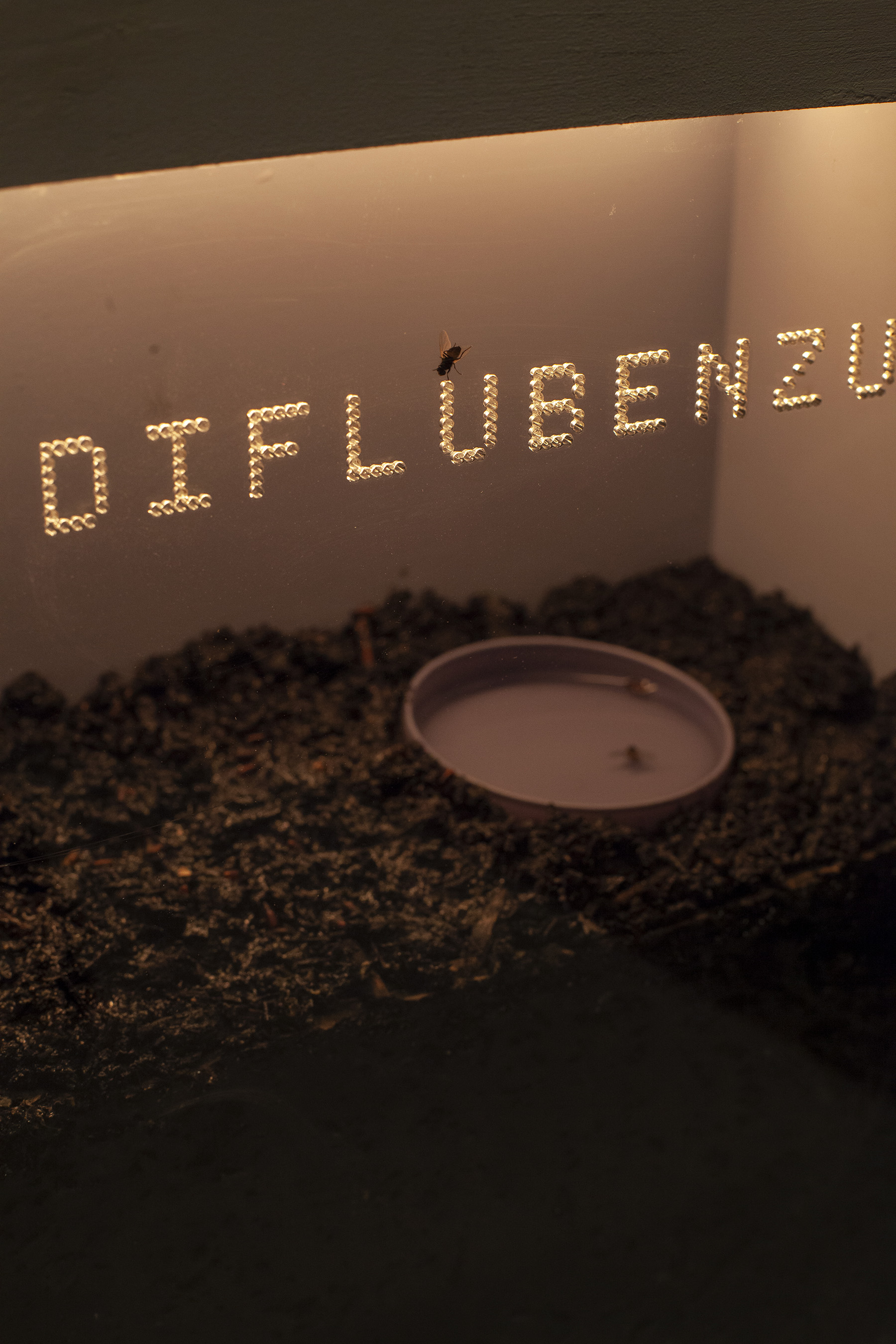

Sometimes the viewer arrives belatedly, and is confronted with only traces of a prior exchange. This is indexed in one case by bird feces coating the gallery floor; in another by two goldfish suspended in plastic bags; in a third, by a bird’s corpse laid delicately on a pile of white fleece blankets. At other times, the intimation of a set lure waiting to be tripped holds the string of time taut: honey drips through plastic tubing; doe urine seeps down into rich, dark soil; rosemary wafts its camphoraceous scent; maple syrup glides over stainless steel; a pool of golden orange apricots languishes stickily. These substances traverse sensorial registers, moving from the ground into its depths and up through the air, their circumlocutions slicing routes across space to inhabit and invade non-human and human animals alike.3

The viewer’s body in the gallery space becomes the architecture around which this choreography is orchestrated, like the person in this viral Tik Tok video, who, over a period of many months, earned the trust of a hummingbird to sit and drink in their presence. Our bodies are not mere seeing machines; they occupy space as critical components of the work’s signification, adding layers to its embodiment. We maneuver these liminal spaces, so redolent with contact and other intimacies. We partake. We move with trepidation, with a heightened awareness of the perils and pleasures inscribed in these scenarios of ensnarement. A great deal is at stake, playing out before us in a compelling mixture of familiar and unfamiliar terms.

3 I am thinking of Mel Chen’s work on chemical intimacies in their many forms. See: Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect (Duke University Press, 2012).

*

Text formed by Tobi Kassim and Audrey Ryan

A flythrough

Whose means are piped through

A denatured byproduct

Trace infiltrates through waste

Justifly®

Often, we are so busy imagining ourselves as apparati, as prosthetic for this encounter between the bird and its nectar — even as an armature facilitating a meeting of two things — that we may, at first, look away from our own entrapment. We walk with felicity along the prescribed path, we lean toward and then away, we consume, excrete, consume, excrete. Hunter and hunted, pursuer and prey — these relations coalesce and their distinctions collapse, becoming tautological at a physical level, as what captures us allures us, and what we escape is also that which we pursue.

Thank you to those who helped me bring this project to fruition: Kevin Hernández Rosa, Tobi Kassim, the Kesslers, Desmond Lewis, Thomas and Alexis Ryan, Anahita Vossoguhi, and a very special thank you to Riley Duncan for all his support.

audreyhryan.com